In the diverse world of diets, few have garnered as much attention as high-fat diets. At a glance, such diets are laden with fat, often relegating carbohydrates to the backseat. While many may opt for this nutrition strategy to induce rapid weight loss or manage specific health conditions, there’s an undeniable link between one’s diet and overall health, with benefits and potential pitfalls.

Understanding Gut Dysbiosis

At the core of our bodies lies a diverse ecosystem known as the gut microbiome. This conglomerate of bacteria plays a monumental role in various aspects of our health. However, maintaining a balanced gut microbiome is paramount. Gut dysbiosis, an imbalance in this microbial universe, presents a slew of common symptoms – from digestive woes to changes in mood. What are the long-term effects? Well, they branch out to more profound issues like obesity, heart disease, stroke, and even certain types of cancer.

Role of High Fat Diets in Gut Health

Peeling back the layers of high-fat diets, it’s intriguing to see how these dietary fats can reshape the gut environment. While some fats, like omega-3 fatty acids, are heralded for their health benefits, others can influence the gut’s bacterial composition. For instance, foods rich in saturated fats could diminish the proportion of beneficial bacteria while enhancing those that may not be as friendly to our health.

Connecting High-Fat Diets to Inflammation

Inflammation, the body’s innate response to injury or foreign invaders, is intricately linked to the foods we consume. The narrative of inflammation isn’t solely about the evident redness or swelling but the silent systemic inflammation that meanders its way, influencing risk factors like blood pressure, cholesterol, and insulin resistance. Dietary fats, particularly trans fats, harbor a pro-inflammatory nature, stoking the fires of inflammation and possibly contributing to conditions like type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

Scientific Studies on High Fat Diets and Gut Dysbiosis

The surge in research about gut health has yielded intriguing results. Numerous studies indicate a direct correlation between high-fat diets and shifts in gut microbiota composition. One groundbreaking study using mice as subjects exhibited significant changes in the gut bacteria composition, predominantly in the Bacteroides and firmicutes phylum, when subjected to high-fat nutrition. Such studies underscore the tangible impact of our dietary choices on our gut health.

Dietary Fats vs. Essential Fats

Fats aren’t painted with a broad brush. There’s an essential difference between various types of fats. While some, like trans fats, have a negative reputation, essential fats, found in foods like avocados and nuts, are indispensable for various bodily functions, including maintaining a balanced gut microbiome. Such differentiation highlights the nuance often overlooked in the broader conversation around fats.

When it comes to the gastrointestinal microbiome, most people are either unaware or have very recently learned of it. This is to be expected as it is a relatively new field of research. An obvious question arises: “What have I been doing that can harm the health of my microbiota?” One of the first places to consider is the diet. Can certain diets influence the microbiota in a significant way?

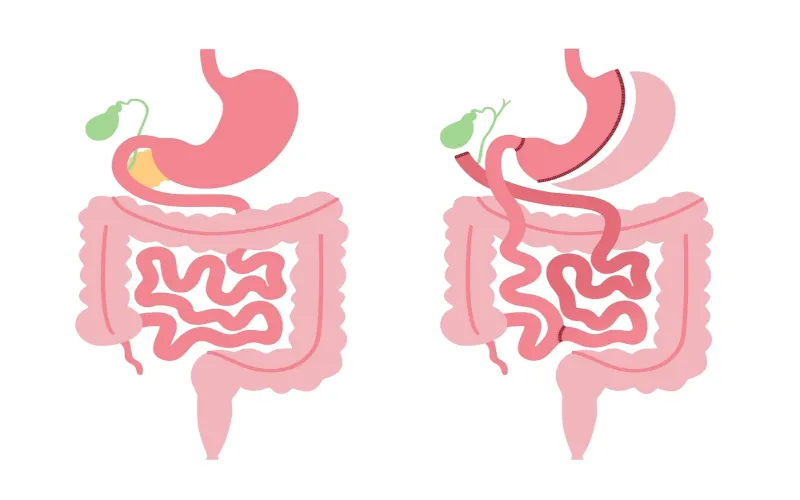

An animal study researched the way dietary fat altered the gut microbiome. They tested three diets: a high-fat diet, a low-fat diet, and a medium-fat diet. It was shown that the different fat content led to variation, which affected appetite control. They added L. rhamnosus into the diets as a probiotic food additive as a separate measure. The probiotic was found to have a therapeutic effect. By modulating the intestinal microflora, the intestinal structure was preserved, and inflammation had been reduced. It is suggested that the probiotic may beneficially alter the metabolism of lipids, which can ultimately be used to attenuate obesity and related metabolic disorders.

Strategies to Counteract Gut Dysbiosis

With the rising awareness of gut dysbiosis and its potential consequences, many seek refuge in probiotics. These beneficial bacteria, often found in fermented foods, hold promise in restoring gut balance. However, beyond probiotics, dietary adjustments remain paramount. Incorporating fiber-rich foods, reducing sugar intake, and moderating fat consumption can all steer the gut microbiome toward a healthier equilibrium.

Lifestyle Habits Amplifying the Effects of High-Fat Diets

It’s not just what’s on our plates that matters. Stress, an all too familiar antagonist in today’s fast-paced world, exacerbates inflammation. Coupled with a sedentary lifestyle, which can hamper gut motility, the effects of a high-fat diet can become even more pronounced, contributing to increased body weight and a host of associated health issues.

The Interplay of Diet and Gut Diversity

Gut microbiome diversity isn’t just a buzzword. It’s an intricate mosaic of various bacterial groups coexisting, each playing a pivotal role in our health. A diverse gut is akin to a thriving rainforest, where each species has its niche, contributing to the ecosystem’s harmony.

Diet’s Role in Microbial Diseases

Certain diseases, specifically those about the gut, can be traced back to our microbiota. Specific diets can either bolster or diminish our defense against these diseases. For instance, certain foods may lead to a decrease in beneficial bacteria, making way for harmful strains to proliferate.

Understanding Bacterial Differences

Not all bacteria are created equal. There are discernible differences in their roles, growth rates, and the metabolites they produce. Some bacteria are adept at breaking down fibers, while others might thrive on sugars or fats. These differences can dictate the overall health of our gut and influence processes like food digestion, weight gain, and even mood regulation.

Effect of Diet on Bacterial Abundance

Every food intake choice leaves a ripple effect on our gut’s bacterial abundance. For instance, a diet rich in processed sugars might boost certain bacterial groups, leading to an overabundance of the proteobacteria phylum. This overgrowth can bring about negative alterations to our gut environment.

Treatment and Cellular Response

Treatment often revolves around dietary interventions and probiotics when gut dysbiosis becomes problematic. But the gut’s response is also cellular. Our gut cells interact continuously with these bacteria; their health directly impacts bacterial growth and diversity. An inflamed gut lining, for instance, might be less hospitable to beneficial bacteria.

Impact on Metabolic Development

The metabolites produced by our gut bacteria play critical roles in our metabolic development. Short-chain fatty acids, for instance, are pivotal for colon health and might affect weight regulation. An imbalance in these metabolites, often due to dietary choices, can precipitate issues like weight gain and altered food intake patterns.

Conclusion

Our understanding of the gut continues to evolve. As we delve deeper into its intricacies, one thing becomes crystal clear: our dietary and lifestyle choices wield significant influence over this complex ecosystem. By acknowledging the profound effects of these choices, we pave the way for better gut health, overall well-being, and a richer life.

FAQs

Can stress alone cause gut dysbiosis without dietary changes?

Chronic stress can negatively affect gut health, potentially leading to dysbiosis even without dietary shifts.

How does sleep impact gut health?

Adequate sleep supports a balanced gut. Chronic sleep disruption can lead to imbalances in the microbiome.

Can gut health impact skin conditions?

There’s emerging evidence that gut health and skin conditions, like acne and eczema, might be interconnected.

Falcinelli, S., Rodiles, A., Hatef, A., Picchietti, S., Cossignani, L., Merrifield, D. L., … Carnevali, O. (2017). Dietary lipid content reorganizes gut microbiota and probiotic L. rhamnosus attenuates obesity and enhances catabolic hormonal milieu in zebrafish. Scientific Reports, 7, 5512. http://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05147-w